|

Author: Sandy Vaile

This article was first published on the Margie Lawson blog on 31/05/22. The average attention span of readers is decreasing (just 8 seconds online, according to research by San Jose University), which is why it’s so important for authors to engage them the moment they step onto the page, so as to speak. Point of View (POV) is one of the techniques we can use to immerse readers in our story world, but it is also a frequently misconstrued and misused concept. It causes all kinds of angst in aspiring authors, who often choose (or accidentally fall into) the omniscient POV, with the misguided belief it will provide more storytelling flexibility. But like every story choice, there are pros and cons. While every type of POV is useful in certain circumstances, I believe mastering a limited POV (particularly when you’re new to fiction writing) will make you a better writer in the long run. Wow, that’s a bold claim! I can already hear the cries of indignation from those who love the omniscient POV. I’m not saying one is better than the other, merely singing the educational benefits of mastering a limited POV. Give me a minute to explain.

0 Comments

Author: Sandy Vaile Originally published by Romance Writers Australia Hearts Talk ezine May 2022 . Why POV is important to your novelPoint of View (POV) characters determine the focus of a story, which is why the decision shouldn’t be taken lightly. It’s not just about who is telling the story but how they are the best character to convey information in an interesting and believable way.

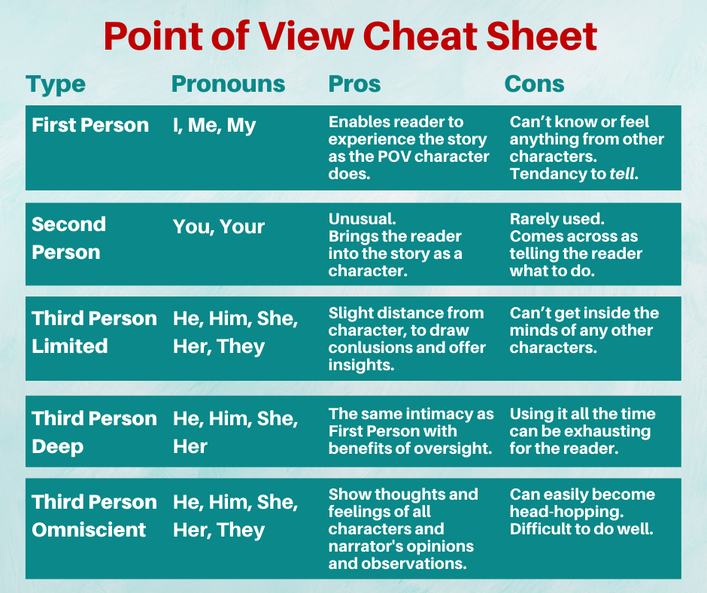

Whether you decide to use first-person, third-person limited or omniscient POV, you will still have to decide which character is going to communicate the story to readers. But how? Author: Sandy Vaile Originally published on the Romance Writers of Australia blog June 2022. Why limited third person POV is the most commonThere are various options when it comes to choosing the right Point of View (POV) for your romance story and they each have benefits and drawbacks.

But why? PurposeThe purpose of these exercises is to explore how it feels to write using Third Person Limited Point of View (POV). This POV option restricts you to one character’s heart and mind at a time, which gives readers time to engage deeply with that character’s desires and struggles. ExerciseAuthor: Sandy Vaile Originally published by Romance Writers of Australia, Hearts Talk ezine, September 2021. The subtleties of story Point of ViewAre you sometimes bamboozled by all of the choices and subtleties of story Point of View (POV)?

You’re not alone. POV is one of the most common errors in fiction manuscripts and even after reading explanations, authors are often still unclear. Should they choose first person, second person, limited third person or omniscient? Which one is right for their story? The mind boggles. Today we’re going to explore the difference between Point of View and Perspective and the whole reason behind applying them to fiction. I’m not going to go into the different types of POV or how to use them, but will:

|

Fearless ProseEmpowering aspiring authors to confidently write novels they're proud to publish Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

© Sandy Vaile 2012-2024 |

Contact and Privacy Policy - About Sandy |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed