|

Author: Sandy Vaile Previously published on the Writers in the Storm blog 02/11/22 Every story has a beating heart that gives it purpose. It’s the vision that keeps all the working parts of a novel focused on what really matters, enabling the author to outline more easily and write a purposeful story. But how can you be sure your story has one (and if it hasn’t, grab the defibrillator and shock it into being)? What is the heart of a story?Plots are the mechanism for moving characters through a series of events towards a goal. The heart of a story is its very reason for existing. The reason a specific author wants to tell a particular story. It turns a common idea into a unique journey, based on what interests the author and why.

At the heart of every story is a theme that runs throughout, which colours the characters and flavours the narrative and conveys the author’s message in a way that affects readers deep in their souls.

0 Comments

Author: Sandy Vaile Previously published on the Writing and Wellness blog 03/08/22. After more than a decade of writing and teaching fiction, I have the luxury of looking back on my journey (thus far) to see where I could have done things differently, to heighten enjoyment and expedite my arrival at the place I am now. And I’m going to share those insights with you today. I’m Sandy Vaile, an author of fast-paced romantic suspense for Simon and Schuster US and a fiction coach who is empowering modern writers around the globe to write stories they're proud to share with the world (one author at a time). If only I'd known the truthThere is limitless information on the internet about how to write and publish a book and yet thousands of authors struggle to find their place in the industry. I believe this is because the creative process isn’t something that can be pigeon-holed and contrived. Original ideas flow from our imaginations and no two minds or lives are alike.

If only I’d known a few truths when I started this journey, it might have made it easier and saved me a heap of anxiety. Author: Sandy Vaile How is the environment relevant to fiction coaching?When you think fiction coach, your mind probably doesn't automatically leap to environmental sustainability, does it? I have to admit that I hadn't considered how my own environmental beliefs might support business efficiency and values either. But last night I attended a fantastic Southern Business Networking and Mentoring event in McLaren Vale, and learnt how businesses can become more environmentally sustainable by implementing a circular economy model of production and consumption.

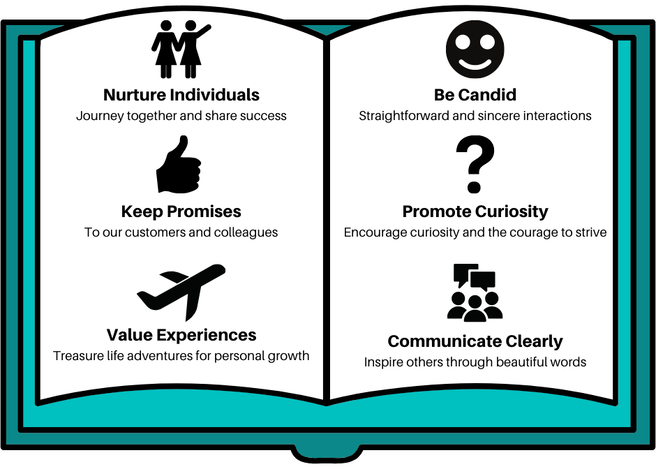

My Business and Environmental ValuesThings I already in my home, which have a positive impact on my business efficiency and support my personal values: ♻️ Reuse ♻️ Recycle as much household waste as possible ♻️ Look for environmentally sustainable products when making purchases ♻️ Run my house on rain water for part of the year ♻️ Support my electricity needs with a solar system ♻️ Water the garden using tank water And, because I am always one to be stretching my limits, in the future I'd like to explore: 🌻 Composting food scraps 🌻 Investing in a battery to store solar power I'd love to hear what actions you take to support environmental sustainability in your life. Drop a comment below. Below are the values that guide Sandy Vaile as she supports aspiring authors across the globe to write fiction stories they are proud to share with the world.

If you'd like to learn more about how Sandy can help you achieve your fiction writing goals, grab a time in her diary for an obligation free chat. Character Development ExercisePurposeThis exercise has been designed to help you see your main characters in a different light, giving you a deeper understanding of who they are, what drives them and how they would react in certain situations.

Author: Sandy Vaile Previously published on the Writers In The Storm blog, August 2022. One of the fastest ways to alienate readers is to get your facts wrong, which can feel like an overwhelming responsibility when writing a story. But how far would you go to bring authenticity and interesting elements into your story? Do You Need to Research for all Fiction Stories?If you’re writing anything longer than a short story, you are bound to need to do some research.

I’m going to demonstrate how research can benefit all stories, and then we’ll peek over the shoulders of a few authors to discover the lengths they’ve gone to, in the name of fiction research. |

Fearless ProseEmpowering aspiring authors to confidently write novels they're proud to publish Categories

All

Archives

May 2024

|

© Sandy Vaile 2012-2024 |

Contact and Privacy Policy - About Sandy |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed